What impact has the Russian invasion of Ukraine had on European attitudes to NATO?

Support for membership has risen, as has the belief that NATO would beat Russia in a potential conflict

Ukraine first applied to join NATO in 2008, in the hopes of avoiding exactly the situation in which it finds itself now. For many nations that are already members, the Russian invasion of Ukraine has reiterated the importance of the NATO alliance to their security, and has forced other nations like Sweden and Finland to look again at remaining outside the organization.

A new international YouGov survey, conducted in Great Britain, Germany, France, Spain, Italy, Poland, and Sweden, explores how attitudes towards NATO have shifted in response to the recent crisis.

Support for NATO membership has increased following the invasion of Ukraine

NATO membership was generally favoured in those countries surveyed that were already members, and has only become more so since the Russian invasion.

In Britain, support for NATO membership rose from 59% in March 2019 to 68% in March 2022*, and in Germany from 54% to 64%. Please note that this question used a five-point scale, including a “neither support nor oppose” option.

In France, support for membership increased from 39% to 47%, while opposition remained constant (15-16%). The number who neither support nor oppose NATO membership is largely the same, at 25-27%, while the number unsure has fallen from 20% to 12%.

In Sweden, which has long debated NATO membership but remained outside of the alliance, support for joining had increased from 36% in 2019 to 44% in early March. At the same time, opposition fell from 27% to 22%, while 22% neither support nor oppose (largely unchanged from 21%).

Although not surveyed in 2019, the results show that support for NATO membership has increased in Spain and Italy since the early days of the invasion.

On 25-28 February, 44% of Italians favoured NATO membership and 14% opposed. Two weeks later, on 10-15 March, backing for NATO membership had risen to 51%, with 16% opposed. Just over a quarter (26-27%) neither support nor oppose membership, with the number of don’t knows falling from 16% to 5%.

Likewise, in Spain, support for NATO membership rose from 53% on 25-28 February to 64% on 9-10 March. Opposition stood at 12-15% in both polls, while the number neither supportive nor opposed fell from 23% to 18%.

This was our first poll on NATO conducted in Poland, and finds 77% there support NATO membership. One in eight (13%) neither support nor oppose, while only 3% are opposed.

Are people willing to commit to collective defence?

Underpinning the NATO alliance is a mechanism known as ‘Article 5’, which states that an attack on one NATO member will be considered an attack on all members. It has only been invoked once in history, by the US after the 9/11 terror attacks.

Article 5 obliges NATO members to come to one another’s aid, and the majority in each of the countries surveyed (58-81%) support their country maintaining this commitment to protect their allies in principle.

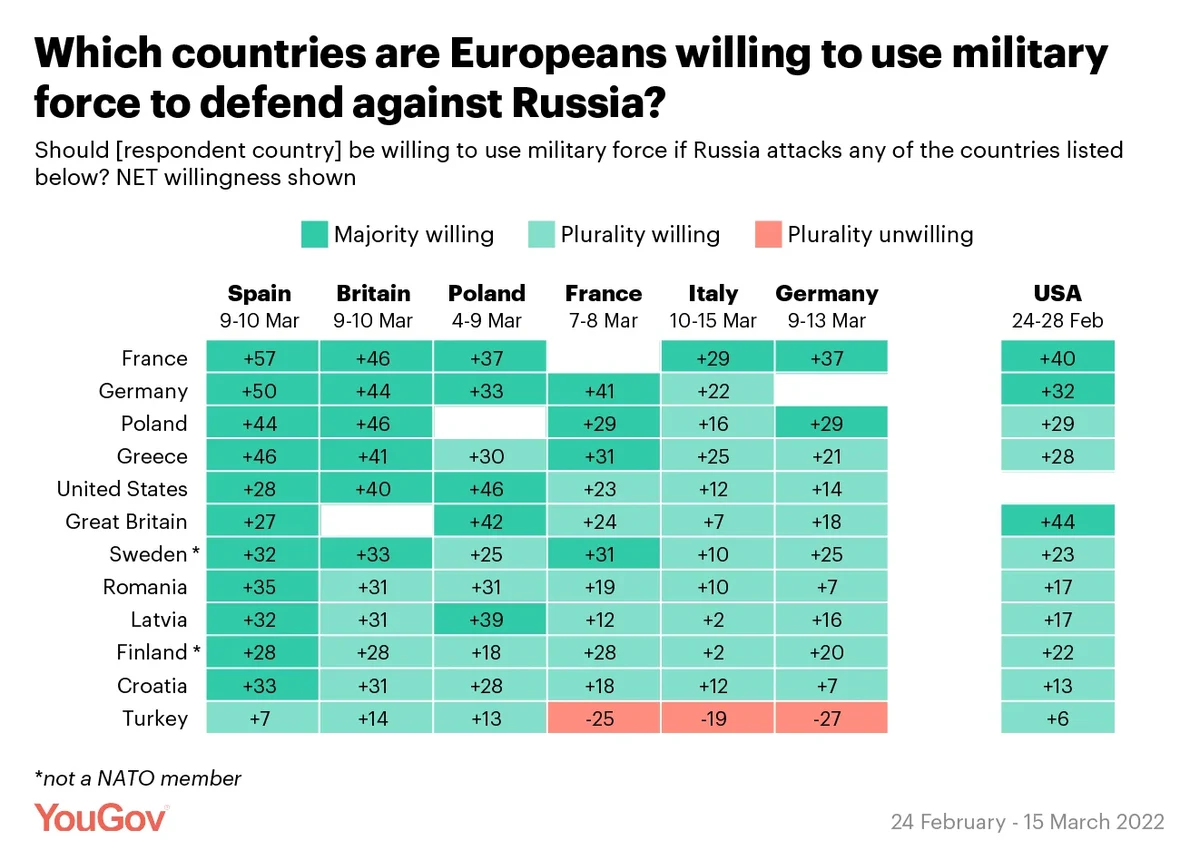

But are they willing to do so in practice? When we ask Europeans whether their country should be willing to use military force to come to the aid of specific countries in the event of a Russian attack, these numbers fall.

Europeans are most willing to see their country protect France, the only country we asked about where more than 50% in each nation surveyed say should be protected (51-71%). Germany comes second, at 48-66%.

Poland also ranks highly, with 44-59% willing to defend it, compared to 42-61% for the United States and 39-59% for Great Britain.

At the bottom of the list is Turkey, itself a NATO member. Fewer than half in each NATO country surveyed wish to use their national military to protect Turkey from Russian attacks (22-40%).

While many of these figures are below 50%, that is not to say that people are unwilling to come to these countries’ aid. In the vast majority of cases, more people think that their country should use military force than not in the event of a Russian attack on that other country. The exception is Turkey, which Italians, Germans and French people would generally not countenance defending – and by wide margins.

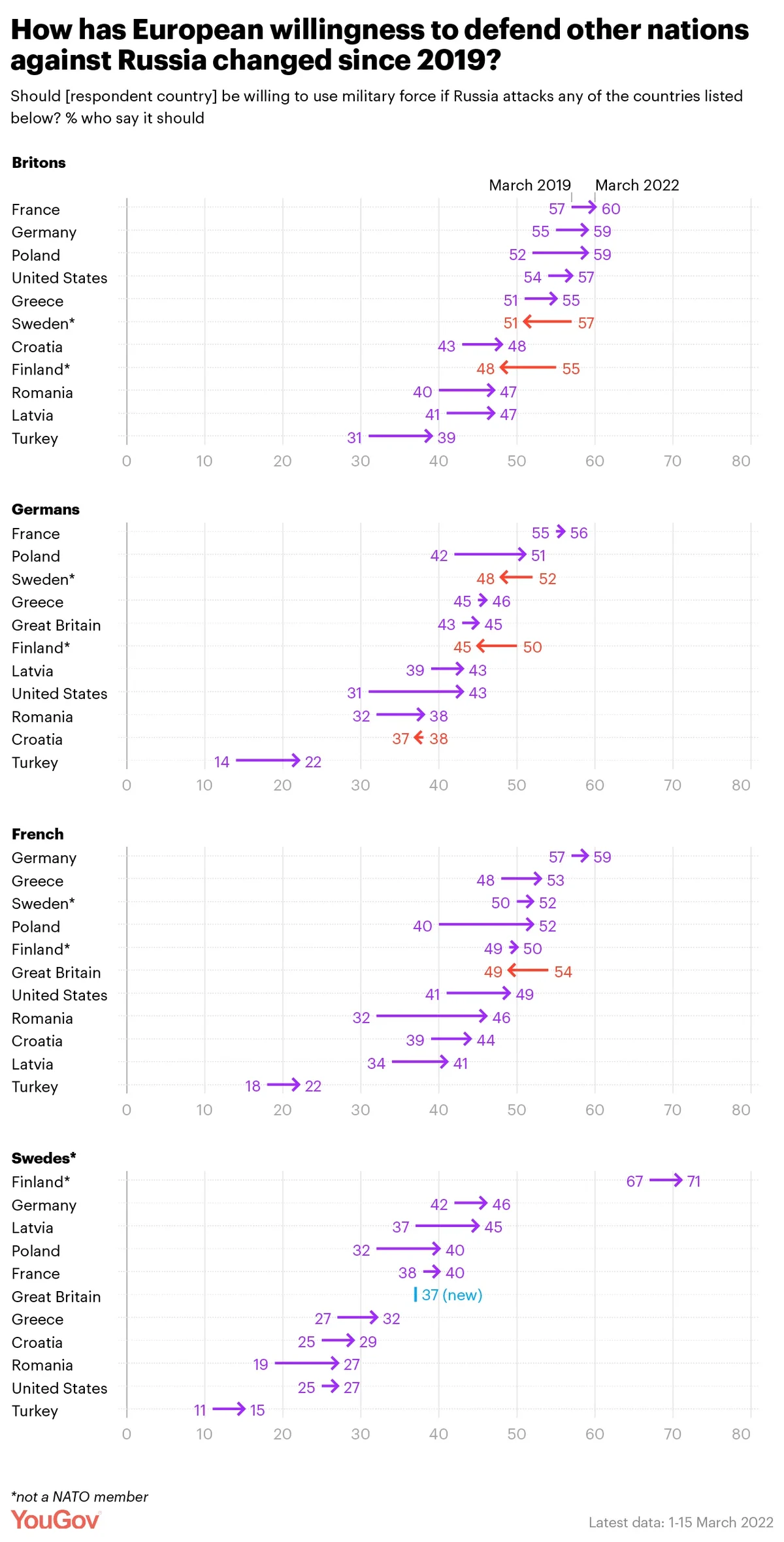

Compared to 2019, there have generally been small to moderate shifts in willingness to protect the countries listed. The exceptions are in Britain and Germany, where people are less willing than they were to defend non-NATO members Sweden and Finland, and in France, where people are less willing than they were to defend Great Britain.

Europeans are even more likely than before to see NATO as still important to the defence of the West

During Donald Trump’s presidency, the US leader called into question the necessity of NATO and was reportedly planning to withdraw from the alliance. Following the Cold War, there have been many times when the continued existence of NATO has been queried, being that it was set up to defend against the now-defunct Soviet Union.

Nevertheless, in 2019 Europeans still tended to think NATO had an important role to play in the defence of Western countries, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine has convinced more still that this is the case.

The biggest jump has taken place in non-member Sweden, where two thirds (66%) now see the importance of NATO’s role, up from 50% in 2019. There has been a similar shift in Germany (from 53% to 66%), while a majority in France are now also convinced (54%, up from 42%). In Britain, there has been a 10pt increase since 2019, from 59% to 69%.

There has likewise been a sizeable increase since the early days of the invasion in Spain (from 58% to 66%) and Italy (45% to 54%). Poles are the most likely to consider NATO important, at 76%.

How serious a threat do Europeans consider Russia to be?

Unsurprisingly, Europeans are now far more likely to see Russia as a serious threat than they were prior to the invasion. In each country surveyed, more than half of those with a view rated Russia an 8/10 or higher in terms of being a serious threat to their nation. In Poland, most people (57%) rate Russia a 10/10 threat.

In those countries also surveyed in 2019, this represents a huge shift. Back then, four in ten Swedes (40%) and just over a third of Britons with a view (37%) rated Russia 8/10 or higher. This figure was even lower in France and Germany, at 23% and 19% respectively. In fact, at that point most Germans (57%) and half of French people (48%) rated Russia a 5/10 or lower – figures comparable to the perceived threat from the USA!

Who would win in a war between NATO and Russia?

In the event that NATO and Russia did come to blows, there is confidence among the publics surveyed that NATO would emerge victorious. The French and Italians are the least sure, but even then the number who say NATO would win (45-48%) far outweighs the number who think Russia would triumph (14-16%). Poles are the most confident, at 78% to 5%.

The underperformance of the Russian armed forces in Ukraine has clearly impacted perceptions of Russia’s might. For instance, whereas in 2019 29% of Germans thought that NATO would win, that rose to 36% in the immediate aftermath of the invasion, and further to 50% in our most recent poll there.

Likewise, in Britain expectations that NATO would win rose from 41% in 2019 to 58% now, while in France they have gone up from 33% to 45%.

*Separate YouGov tracker data, which uses a question that does not include a ‘neither support nor oppose’ option, found support in Britain at 79% in early March. This represents a similar increase in support for membership as found in this survey

This article was updated on 22 March 2022 with updated US data on willingness to defend other countries

See full results for February (post-invasion) here and March here