What should the EU be?

A major YouGov study of citizens in 13 member countries looks at attitudes to the EU

In April of this year YouGov conducted a major international survey for the European University Institute’s European Governance and Politics Programme.

We surveyed more than 21,000 people across 14 European countries: Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Lithuania, Netherlands, Poland, Romania, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. With the exception of the UK, all of these countries are EU member states.

The data provides key insights into the kind of vision people across the EU have for the body’s future. YouGov has now taken a detailed look at whether people think the EU should be…

- A protective Europe, global Europe or market Europe?

- A source of solidarity?

- More active?

- Raising taxes and spending?

- More flexible with its members?

- A military power?

- The top global power?

What should the EU be: a protective Europe, global Europe or market Europe?

We asked people in each of the three countries which of the following types of Europe they would prefer to live in:

- a protective Europe that defends the European way of life and welfare against internal and external threats;

- a global Europe that acts as a leader on climate, human rights and global peace; or

- a market Europe that stresses economic integration, market competition and fiscal discipline.

In 10 of the 14 countries people tended to opt for the ‘protective Europe’ option, including a majority of Greeks (57%).

Only four opted for the ‘global Europe’ option, including Germany (37%) and the UK (40%). Swedes were most likely to back this option, at 42%.

No country opted for ‘market Europe’. The highest score it achieved was in Italy, at 25%.

What should the EU be: a source of solidarity?

From time to time it is likely that individual EU member states may face a crisis and require assistance from their neighbours.

People in all 13 EU countries tend to support giving “major help” to another EU country that had been stricken by natural disaster, an epidemic or public health crisis, or military attack. Additionally, all countries except Finland would be willing to help in the event of a climate change-related problem.

The picture is more mixed when it comes to helping countries affected by a refugee crisis or left behind technologically, while people in most countries tend to be against helping out when it comes to unemployment or a debt crisis.

Southern and Eastern European nations are noticeably more likely to be willing to help than their Northern and Western counterparts. Almost all Southern/Eastern countries were willing to help in all circumstances (except Hungary for major debt or unemployment crises).

By contrast, in none of the Northern/Western countries are people willing to offer assistance in the event of a major debt crisis. With the exception of Lithuania, they are similarly unwilling to help in the event of a major unemployment crisis.

Most are also reluctant to help neighbours left behind by technological advancement.

It is clear that Europeans think that the EU should serve to co-ordinate activity on behalf of members to assist other member states. In all examples, people would vastly prefer to give assistance through an EU-led initiative, rather than their country acting unilaterally.

Likewise, in all cases almost all countries prefer to assist via a permanent system set up to help EU members finding themselves in these kinds of crises, instead of providing help on a case-by-case basis. The Dutch and the Danes were often closely split on this issue.

There is a notable division between the countries surveyed on whether they would expect to be net beneficiaries of such structures. In Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Sweden and the Netherlands, people expect that their country will end up paying in more money than they get out. In Greece (66%) and Spain (63%) in particular people believe these structures would hand back more in assistance to them than they had contributed.

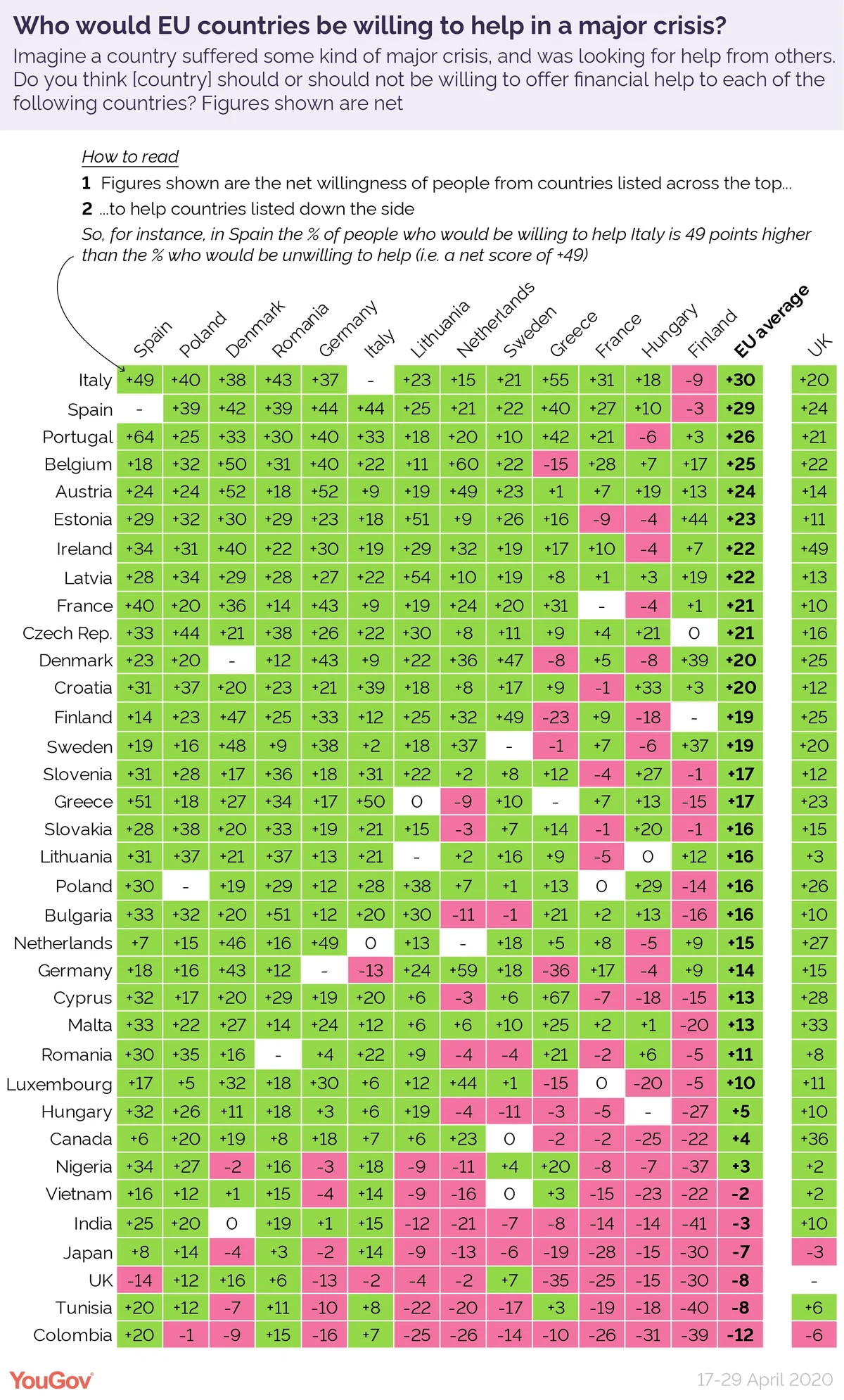

All of these questions were asked about a hypothetical EU member state. But there is reason to believe that sentiment will differ wildly depending on which country becomes stricken by catastrophe.

For instance, while people in almost all of the EU countries surveyed (Finland being the exception) would be willing to give financial help to Italy and Spain – and by wide margins – people are much more reluctant to help countries like Romania and Hungary.

These results also demonstrate quite how far the UK has alienated its European neighbours. Of the 35 countries we asked people whether they’d be willing to assist, the UK comes joint 33rd – tied with Tunisia and above only Colombia.

Only in Greece, Denmark, Poland and Romania do more people than not say they would be willing to give the UK financial aid in the event of a major crisis.

This is not simply the case that the UK is a rich country and so people won’t donate on the basis that the UK can afford to look after itself: people are far more willing to provide financial assistance to the other top wealthy European countries Germany and France.

All of the data described above has been on people’s opinion about offering assistance in exceptional circumstances. When it comes to doing so as a matter of routine, i.e. through redistributing money raised through taxation across the EU, Europeans are far less reluctant.

When asked whether or not they would want some of their tax money being spent on helping people in other EU countries, almost half or more in every country (48-72%) said no.

By contrast, when asked the same question about some tax money being spent helping people in places like Africa, the results were more mixed. In seven of the 13 EU countries the most common response was that people would be happy for the government to use their tax money in foreign aid.

This could indicate that people see Europeans as too well-off to be worthy of financial assistance, in contrast to poorer places across the globe.

None of this to say there is no appetite for a redistributive EU. When asked on a 0-10 scale how far money should be spent exclusively by member states or pooled by the EU, the proportion answering “10 - Spend resources equally on all countries and all people in the European Union” was fairly substantial – as high as 27% in Romania, 23% in Greece and 22% in Italy and Poland.

Nevertheless, in France, Germany, the Netherlands and the Nordic countries in the study, only 5-9% of people felt the same way.

At the same time, however, there is very little appetite to exclusively hoard resources: only 5-11% of people in each country answered “0 - Spend resources only on own country and own people”.

What should the EU be: more active?

Asked what areas they would like to see the EU be more or less active, in net terms the most welcome areas for greater EU activity are immigration and “the economic situation”, as well as climate change and health and social security.

The areas in which people tended to be want the EU doing less were taxation, housing and energy supply.

Only 1-5% answered “none of these” for areas where the EU could be more involved, while 11-24% didn’t want the EU less involved in any area.

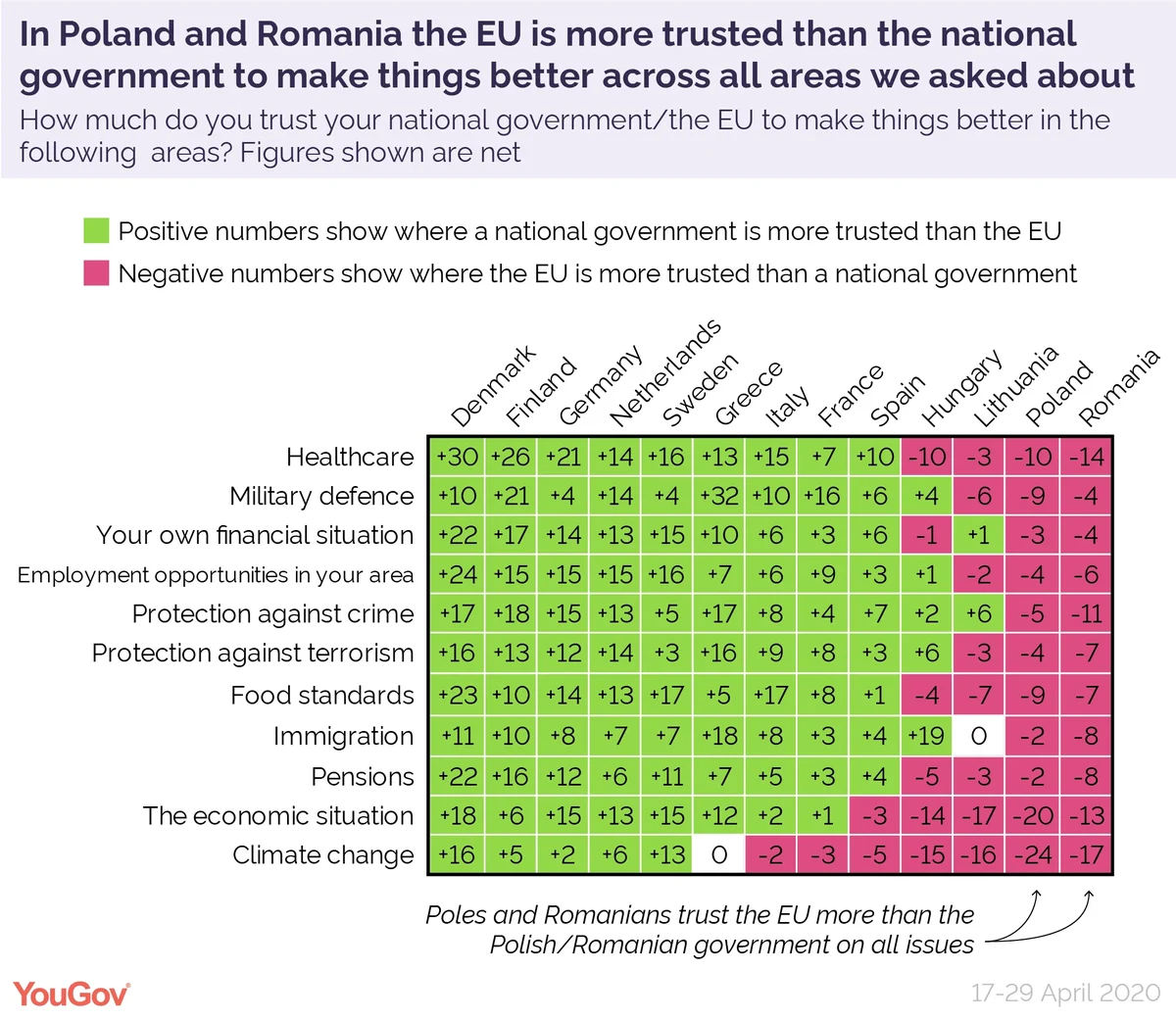

It is perhaps no surprise to see people most likely to want greater involvement when it comes to the economic situation and climate change, given that these are the areas where countries trust in the EU performs most favourably when compared with trust in national governments.

In seven of the 13 EU countries people are more likely to say they trust the EU on climate change than they are to say they trust their national government, with Greeks also exactly tied. This is also the case for five countries when it comes to “the economic situation”.

This is less obviously the case for immigration, the area Europeans most commonly want the EU to be more involved. This could possibly indicate a perceived failure of EU attempts to help in this area so far, or a recognition that the EU’s pro internal migration stance runs counter to many peoples’ own stance on immigration.

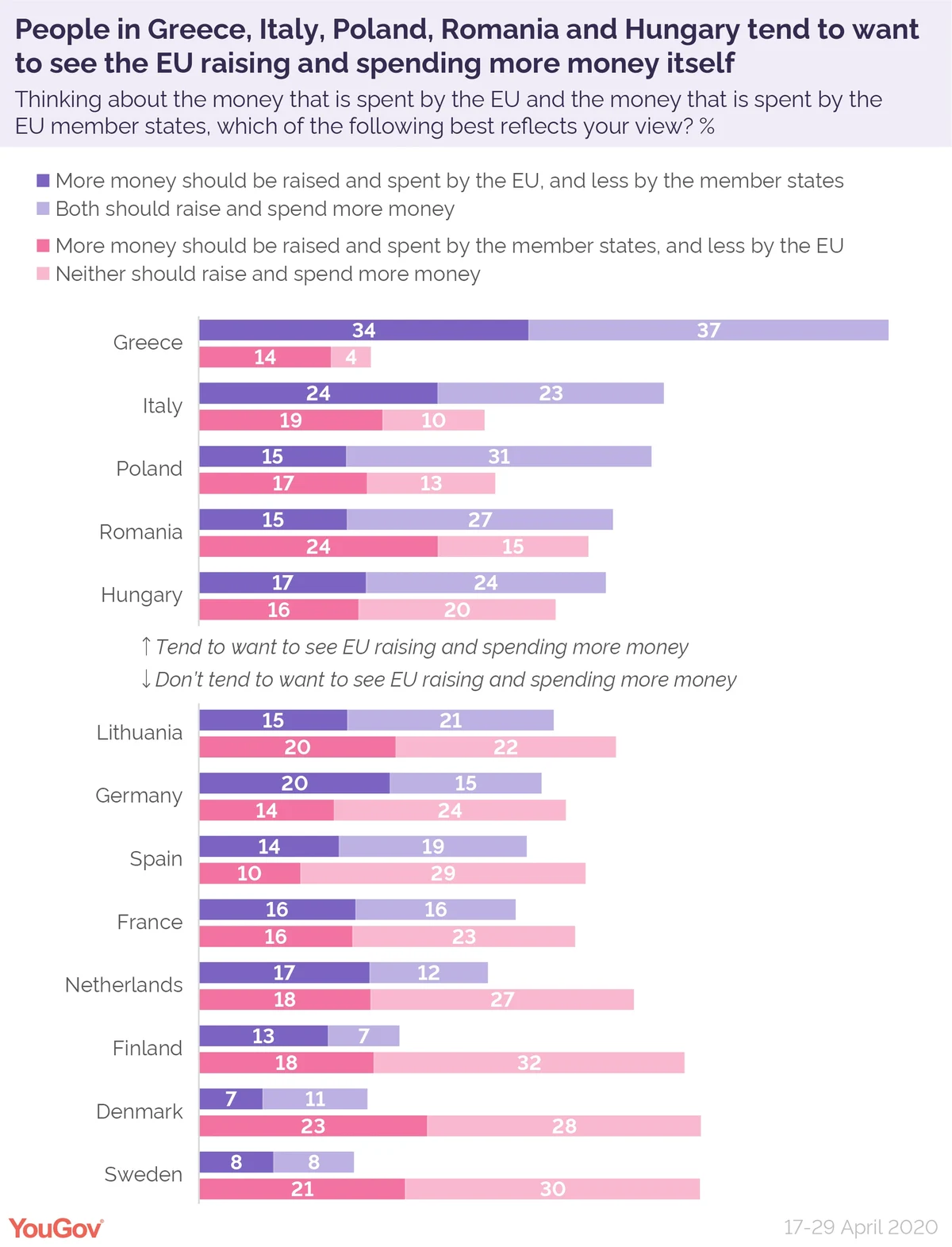

What should the EU be: raising taxes and spending?

In only five of the 13 EU nations surveyed do people tend to want to see the EU raising and spending more money: Greece, Italy, Poland, Hungary and Romania.

While Europeans are reluctant for greater EU involvement in taxation, it could be that they’re thinking more of taxes that directly impact themselves, such as income and consumption taxes.

Because when asked about four additional areas in which the EU could impose taxes that wouldn’t directly impact citizens, people across the 13 EU nations were often strongly supportive. In every country people support new EU taxes on business profits and carbon emissions.

In all countries bar Sweden there is also support a tax on financial transactions (like trading shares), and people everywhere except Sweden and Denmark supported a tax on the revenue of large internet companies.

What should the EU be: more flexible with its members?

Ever since the EU started to expand into Eastern Europe the prospect of a ‘two-speed Europe’, whereby some states are allowed to move more slowly towards integration, has been debated as a way of helping accommodate the needs of a larger and more varied EU membership.

The most staunch Europhiles strongly oppose the concept, seeing it as an impediment towards “ever closer union”, the key concept underlying the EU.

The results show that there is little opposition to a two-speed Europe across the EU countries surveyed. Opponents are most numerous in Greece, where one in five (21%) are against the principle. This is nevertheless far lower than the 37% who support allowing integration at various speeds. Opposition in other countries is lower still, standing at just 5-14%.

On the issue of opt-outs – again anathema to ever-closer-unionists – people in all EU countries except Germany were more in favour of allowing them than not.

Support is highest in Denmark at 52%, unsurprising given the nation has itself opted out of joining the Euro. By contrast only 21% of Germans support opt-outs for members, compared to three in ten (31%) who are opposed.

Regarding the common currency, most countries agree that all EU should members should have to join the Euro eventually – even in Hungary and Romania which are not currently members of the Eurozone. However, Denmark and Sweden – both not currently Eurozone members – are strongly against, while Poland (also not a member) is split 32%/33%.

What should the EU be: a military power?

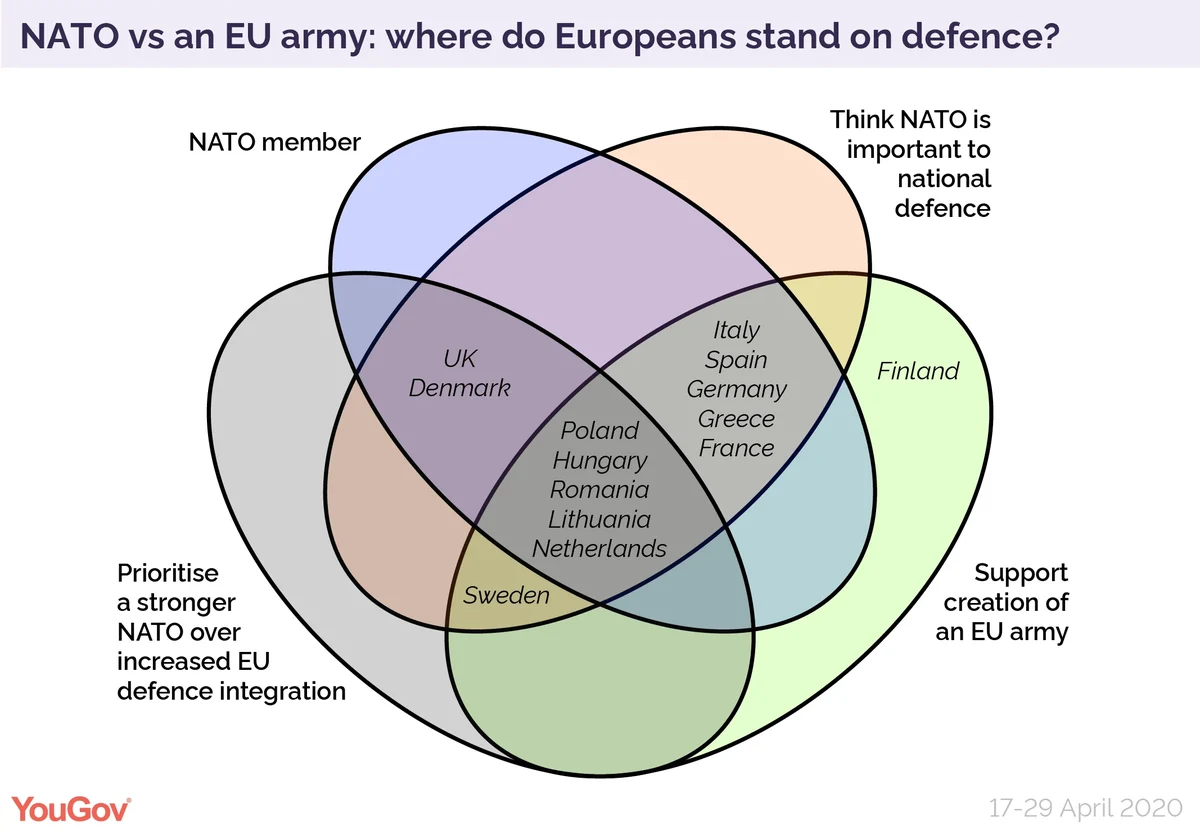

Nevertheless, it is clear that people across Europe see NATO as important to national defence. In most countries a majority of people say NATO is still very or fairly important to their country’s defence. The only country where people tended to see it as unimportant was Finland, which is not a NATO member.

There is, however, division on whether a stronger NATO or greater EU defence integration is the best path to take. Given their opposition to an EU army, the British and Danes are unsurprisingly more pro-NATO on this question. In this they are joined by Romania, Lithuania, Poland, the Netherlands, Hungary and Sweden (even though this latter country is not a NATO member).

Greece, Germany, France, Spain, Finland and Italy all prefer to develop European Union defence systems further.

This breakdown mirrors that from a separate question asking how countries should respond in the event of an attack on an EU member state. The only exception is Germany, where 50% said they should help via NATO compared to 27% who said an EU-led response should take place.

As with the willingness to help in other crises, opinion is heavily subject to the country requiring aid. In none of the countries do people particularly want to come to Turkey’s aid (despite the legal requirement of most to do so as NATO members). Most countries likewise aren’t willing to help Albania (another NATO member), and opinion is mixed when it comes to Romania (both an EU AND a NATO member).

The prospect of defending Greece, Latvia and Norway (the latter a NATO member but not in the EU) is far less controversial, with a large majority of the countries studied being willing to stand alongside them. Hungarians proved the only exception, saying they would not support sending forces to defend any of the countries named.

What should the EU be: the top global power?

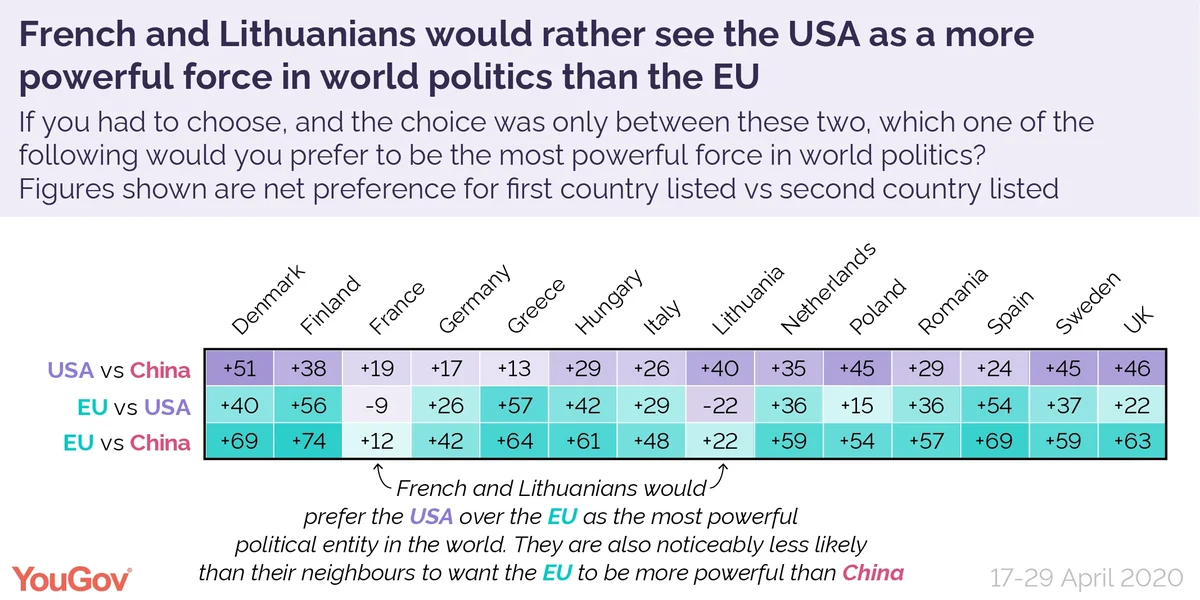

Currently the two greatest world powers are the USA and China. In all countries people would prefer the USA to be the more powerful, although the level is not as emphatic as it may once have been – between 30% and 54% in each country couldn’t pick between the two nations.

But what if the EU was in contention? When asked to choose between the EU and China the answer is universal: every country would prefer the EU to be the greater power.

This is generally the case when contrasting the EU and USA, with two exceptions: the French and Lithuanians would prefer the USA to be the more powerful entity.

In all countries surveyed people were more likely to see China as the more powerful economic rival to the EU, while the US is seen by more as the stronger cultural or political rival to the EU (although in almost all cases people were more likely to say that both the US and China are major rivals).

This survey was conducted by YouGov for the European University Institute’s European Governance and Politics Programme. The results are available here, and the EUI discusses them in their publication ‘EU Solidarity in Times of Covid-19’