China struggles for Western hearts and minds

The Chinese Government is on a global campaign to boost its popularity. But as national polling in five countries suggests, it still has a serious image problem among the Western public.

Over the past fifteen years, the Chinese government has invested heavily in promoting a positive international image. This includes developing a range of foreign language news outlets and public relations campaigns, encouraging international students to pursue their education in China, and establishing a network of Confucius Institutes on university campuses worldwide, offering language courses, cultural classes and celebrations to mark Chinese holidays.

Despite such initiatives, however, it seems that many Western voters maintain a significantly negative view of China and its role in the world. This is according to a new five-country survey of public opinion conducted jointly by the YouGov-Cambridge Centre and the Jesus College Intellectual Forum, in support of its Rustat Conference on the subject this week.

The research included nationally representative surveys in Britain, France, Germany, Sweden and the United States. Fieldwork was conducted between 14th February and 19th March, 2019. (See methodology description below)

Respondents were first shown a list of foreign countries, including Canada, Japan, China, Russia, Saudi Arabia and North Korea, and asked if they perceived each one as a threat or otherwise to various aspects of life.

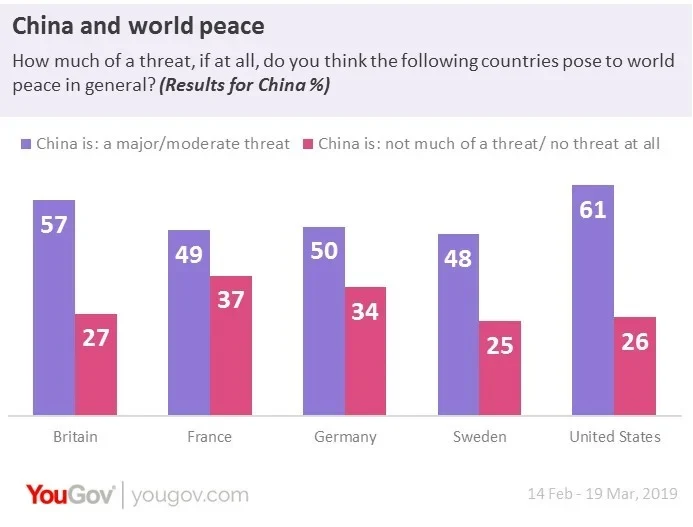

As results show, a majority in the United States (61%) and Britain (57%), along with half in Germany and just under half in France (49%) and Sweden (48%) described China as a threat to world peace.

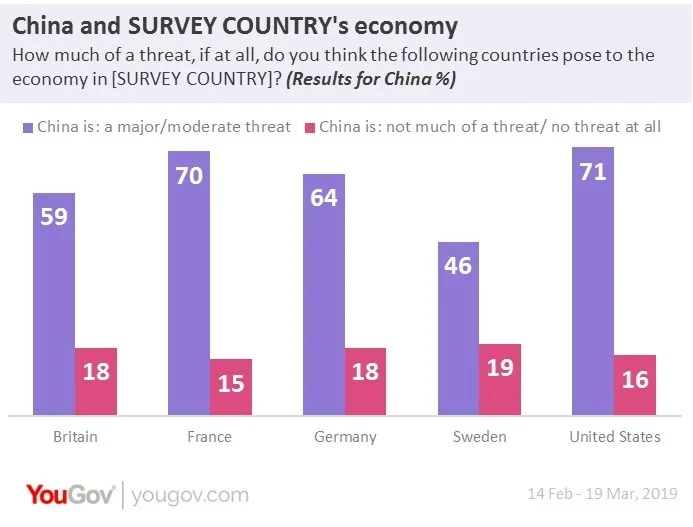

Similarly, the larger portion in all countries described China as a threat to their own economy, including 59% in Britain, 70% in France, 64% in Germany, 46% in Sweden and 71% in the United States. This compared with no majorities saying the same for other countries listed.

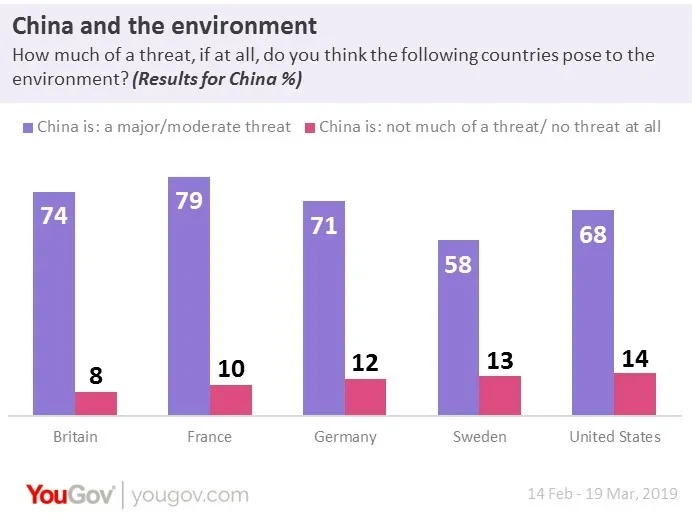

China also came out worst in terms of environmental reputation, with considerably higher majorities describing it as a threat to the environment, compared with other countries on the list. This included 74% in Britain, 79% in France, 71% in Germany, 58% in Sweden and 68% in the United States.

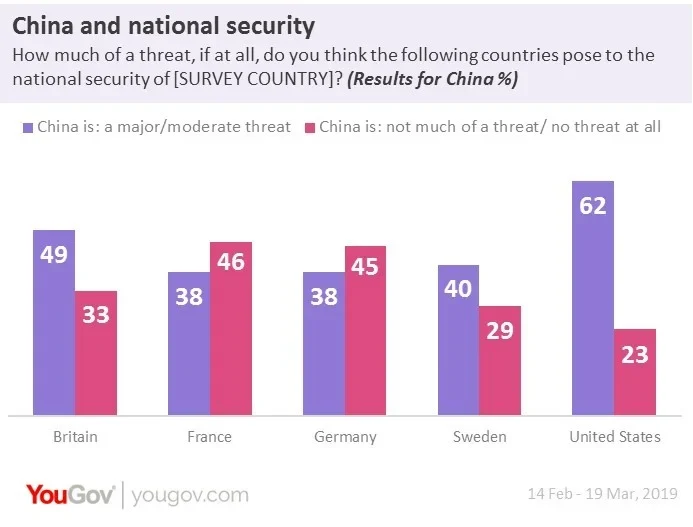

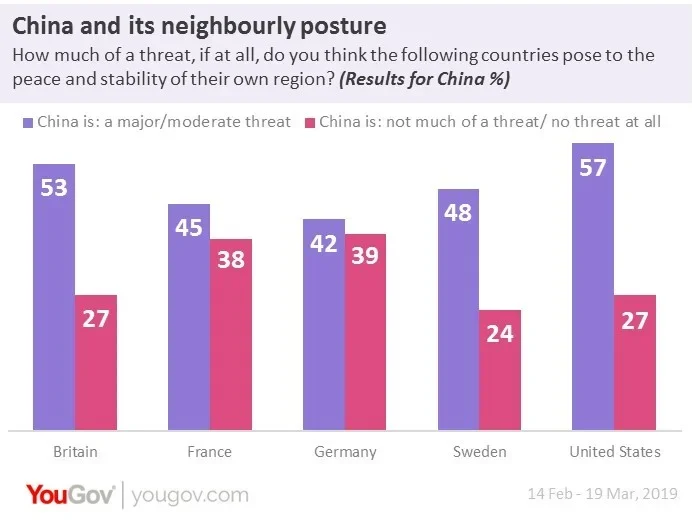

Notably, there was slightly more variance among Western countries when it came to questions of national security and neighbourly posture.

While a majority in the United States and roughly half in Britain described China as a threat to national security, the larger portion in both France and Germany showed less concern, with 46% of French respondents describing China as “not much of a threat” or “no threat at all”, compared with 38% calling it a major or moderate threat. The balance in Germany was near identical, with 45% versus 38% respectively.

Likewise, majorities in the United States (57%) and Britain (53%) described China as a threat to the peace and stability of its own region, compared with smaller but still substantial pluralities saying the same in France (45%), Germany (42%) and Sweden (48%).

As findings further show, China's image tends to be somewhat less negative than that of Russia, Saudi Arabia and North Korea. But it bears notable contrast to the largely benign impressions of Japan and Canada.

For instance, the percentage of those describing China as a threat to the peace and stability of its own region ranged from 42% to 57% across all five sample totals. This compared with a range of 53-71% saying the same for Russia, 48-63% for the Saudi Arabia, and 52-75% for North Korea. By contrast, however, the ranges for Japan and Canada were just 12-17% and 2-10% respectively.

By a similar token, the range among the sample totals for those describing China as a threat to world peace was 48-61%; not as high as those for Russia (56-78%) or North Korea (54-73%) but slightly above that of Saudi Arabia (46-59%) and markedly higher than those for Japan (12-18%) and Canada (2-9%).

Respondents were next asked to say which words or phrases they associate most with four superpowers of world politics, being China, Russia, the European Union and the United States. This included choosing up to four answers from a randomly ordered list of six positive and six negative labels.

On the upside for Beijing, “economic success” and “on the rise” featured in the top four most common descriptions across all countries. Less positively, so did “corrupt” in four out of the five countries (with the fourth most common association in Germany being “reckless” instead). Another word that featured even more prominently, appearing in the top three most common associations with China across all samples was “oppressive”, suggesting perceptions of its political system remain dominant in the country’s international reputation.

Finally, respondents were asked about perceptions of blame in the current US-China trade war and the appropriate place of human rights discussion in their country’s diplomatic relations with Beijing.

It seems the narrative of US President Trump about unfair Chinese trade policy has failed to gain much traction among these Western publics. As the table shows below, only fractions in Britain (7%) and mainland Europe (9% in France/ 5% in Germany/ 10% in Sweden) see China as more to blame than the United States for current trade disagreements. Even within the United States, little over one in four say the same. Instead, 33% in Britain and 39% France are more likely to see both sides as equally to blame, while a further quarter in both countries say the United States is more or entirely to blame. Swedish respondents are more evenly split between those who blame both (28%) or more/entirely the United States (21%), while Germans are more critical of the United States, with 45% seeing it as more or entirely to blame.

Which side, if either, would you say is more at fault in the current disagreements over trade policy between China and the United States? (%)

| GB | FRA | GER | SWE | US | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

China at fault, not US | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 9 |

China more at fault than US | 6 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 18 |

TOTAL CHINA MORE AT FAULT | 7 | 9 | 5 | 10 | 27 |

Both sides equally at fault | 33 | 39 | 27 | 28 | 25 |

US more at fault than China | 19 | 18 | 33 | 14 | 18 |

US at fault, not China | 4 | 7 | 12 | 7 | 4 |

TOTAL US MORE AT FAULT | 23 | 25 | 45 | 21 | 22 |

Neither side at fault | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

None of these | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

Don't know | 33 | 21 | 19 | 37 | 20 |

It is also clear, however, that the larger portion in all samples think diplomatic relations with Beijing should include a focus on Chinese human rights and efforts to persuade its Government to improve them.

This included 66% in Britain, 64% in France, 68% in Germany, 49% in Sweden and 62% in the United States, all variously split between those who think the subject should or should not come at the expense of good Sino trade relations. Only small numbers in each country thought the subject should be avoided entirely in relations with China, as the latter would presumably prefer. (7% in Britain/ 13% in France/ 8% in Germany/ 5% in Sweden/ 11% in the United States)

Sharp power versus soft power

These figures further lend themselves to a general point about public diplomacy in the age of globalised, digital media.

Security analysts are naturally concerned that autocratic regimes have grown adept at targeting Western polities with a fast evolving suite of information operations. This includes planting party-line content and advertorials within independent outlets, marketing state-backed media channels as “alternative” news, cultivating third-party cheerleaders and covertly propagating divisive, social media discourse.

There is a difference, however, between the “sharp power” of media penetration – as the International Forum for Democratic Studies has described it – and the “soft power” of genuine, public appeal or attraction.

As original author of the concept, Joseph Nye notes that soft power still relies on the vital currency of common values, imagined or otherwise. In which case, no amount of tech-savvy nation-branding or alt news dissemination is likely to shift underlying Western regard for the realities of authoritarian government in Moscow and Beijing, or the entrenched rivalry of economic superpowers, or military revanchism in Eastern Europe and the South China Sea.

Hence, for all the current concern about a modern renaissance in autocratic propaganda, the dividend in actual popularity that it pays to its investors remains automatically limited, at least in this part of the world.

Methodology: All figures, unless otherwise stated, are from YouGov Plc. Total sample sizes were: GB =1804; France= 1024; Germany= 2035; Sweden=1515; US= 1247. Fieldwork was undertaken between 14th February and 19th March, 2019. The surveys were carried out online. For each market, the data have been weighted and results are representative of the adult population aged 18+.

Image: Getty