Public opinion and the social media crisis

Many of us doubt that social media is ultimately good for society. Yet it remains hard to see how the worst side-effects of Web 2.0 can be countered.

What a difference a year makes for the reputation of Big Tech.

2017 seemed to start like business as usual, including the annual mission statement from social media czar Mark Zuckerberg, this time praising Facebook for spreading social cohesion and declaring his company’s next task: to make the world a better place by building a global community of informed, inclusive netizens.

But then followed a kind of annus horribilis for Silicon Valley, which saw it variously accused of failing to tackle misleading and illegal internet content, supporting a work culture of chauvinism and sexual harassment, selling out to autocratic censorship, shirking responsibility on tax and gig workers' rights, stifling innovation through market dominance, and flooding Washington with lobbyists to protect its entrenched monopoly.

As the first online age, Web 1.0 was essentially an information portal of static websites that multiplied over the final quarter of the 20th Century. From the turn of the millennium, so-called Web 2.0 marked a shift from access to participation via user-generated content and curation.

No doubt this evolution has empowered us – to voice opinion, share experience, nurture relationships, raise awareness, mobilise the demos, access information, respond to crisis and, of course, to brag and advertise.

But for much of this period, the tech giants have also had it both ways, reaping the fortunes of big business while claiming the halo of pious duty to humankind.

Mr. Zuckerberg and other web billionaires might still believe in the high canon of cyber utopian cant. But the general public evidently does not.

How voters see the Internet

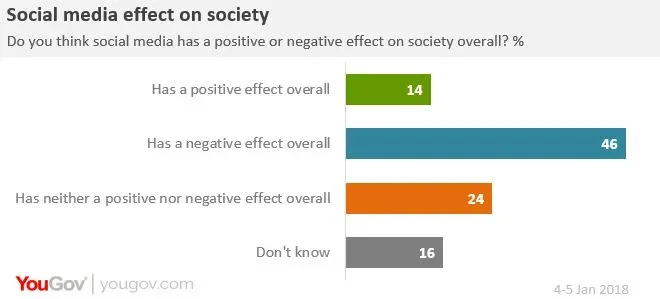

According to research for the YouGov-Cambridge Centre, just 14% of British voters think social media is ultimately good for society, compared with a striking 86% saying otherwise. This includes nearly half (46%) who believe social media has a negative effect on society overall, plus a further 24% who say the impact is “neither positive nor negative” and 16% who “don’t know”.

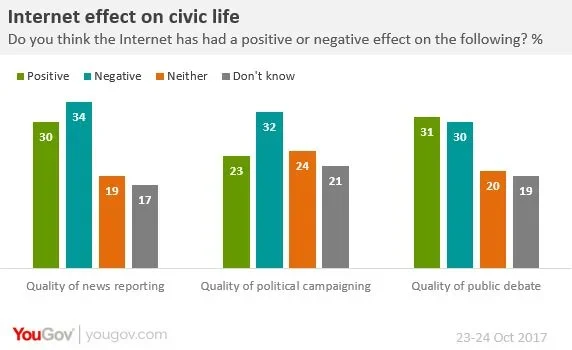

As other polling for the same project shows, many voters doubt the Internet has been ultimately positive for key aspects of civic life such as the quality of news, political campaigning and public debate.

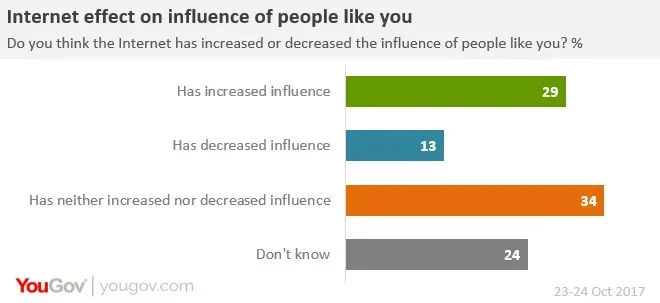

Neither do most people feel personally empowered, it seems, by the digital revolution. Again, about a third (29%) have a positive opinion, saying the Internet has increased the influence of people like them, while the rest take a view ranging from negative (13%) to neutral (34%) to uncertain (24%).

Interestingly, the political left in Britain feels more empowered by the Internet than the right: 41% of the self-described Left say the web has increased their influence, compared with 23% of the self-described Right saying the same. Likewise, 47% of the Left say the Internet has increased the influence of “good ideas for radical change”, compared with only 29% of the Right. A less exaggerated version of this gap can be seen between those who voted Remain (32% for “increased”) and Leave (25% for “increased”).

Age is a likely factor here, with the British Left being generally younger and more digitally engaged. It is notable, however, that matching portions of the Left and Right (45%) tend to agree that the Internet has increased the influence of big business, while majorities in each case think the Internet has increased the influence of “bad ideas for radical change”.

These findings chime with other YouGov research over recent years, showing consistent public scepticism towards both the civic value and governance of the social web.

In cross-country YouGov research for the Reuters Institute (p.22), for instance, we see a wide difference in public faith towards news media and social media, with people far more likely to have faith in the former than the latter, including the US (38%/20%), UK (41%/18%), Canada (51%/24%), Ireland (47%/28%), Austria (40%/27%), Germany (44%/20%) and Denmark (42%/15%).

"Online salience is stubbornly allied to clickbait sensationalism"

Large numbers of British voters have previously told YouGov that social media companies should step up to the duties of publisher, rather than merely platform, in making sure that only genuine news stories are displayed (67%) or shared (62%) onsite. Similar majorities have stated these companies should be doing more to protect from bullying or harassment, and backed the idea of prohibiting anonymity for users.

When it comes to a hierarchy of cyber concerns, furthermore, British voters are discernibly more concerned about the behaviour of private companies than they are of government surveillance.

Frankenstein tweaking?

The incumbent trio of Facebook, Google and Twitter have pledged to do more in stemming the propagation of illegal and misleading content in search results and feeds, or the capacity of inappropriate sites to gain from online advertising. This includes recent announcements from Mr. Zuckerberg about changes to Facebook algorithms, which will deprioritise third-party content in favour of more personal posts or comments, and prioritise links to “broadly trusted” news sources according to the majority verdict of user surveys.

But it still seems hard to imagine how the organic, behavioural characteristics of the social web can now be fundamentally changed.

The very essence of online social networks remains that of a personalised hub, with the ability to prioritise or reduce exposure to content according to preference. Online salience is also stubbornly allied to clickbait sensationalism. What gets posted or gains traction is what generates attention, which is more likely to be emotive, hard-line and truncated for the short attention span. Hence the cyber public space is often one of binary extremes.

Another dogged phenomenon is filter-bubble populism. As author Jamie Bartlett puts it, the Internet has opened up new ways of finding and forming tribes. Research further suggests that netizens are more likely to connect with those who share similar views, while algorithms learn what we like and show us more of the same.

"A key element in the mix is the 21st Century age of victim empowerment"

The noble benefits to enhanced activism are self-evident. But the same occurrence also feeds a tribal form of identity politics, whereby users coalesce into filter bubbles that reinforce predisposition. This doesn't mean we only see content that we like, as is often implied by terms like “filter-bubble” and “echo chamber”. On the contrary, it can elevate the most negative examples of other tribes, explains Bartlett, in ways that not only corroborate our own views but also confirm our worst impressions of others.

Thus alongside warm and cuddly visions of “global community”, the hashtag mentality doubtless helps to accentuate division, often in solidarity against the caricature of a common enemy.

A key element in the mix is the 21st Century age of victim empowerment. The very ethos of digital society has become that of social empowerment and expanded power for the individual. This ethos is doing much to advance a new epoch of accountability and equality. But it also gives a new sense of vogue to the card-carrying status of victim, sufferer or devotee, which can spur a crass intolerance towards difference or nuance of opinion as a way to assert such status.

In so doing, sharing platforms have helped to normalise a new form of swarming anti-social behaviour, which many perpetrators would lack the nerve or incentive to carry out otherwise.

Heuristics and the consensus effect

The academic study of public opinion may add context here. As Walter Lippmann noted in his seminal work on the theory of public opinion, our modern environment is “too big and complex for direct acquaintance” 1. So we reconstruct it in simplified form as a pseudo environment, which requires less information. This environment duly relies on a personal ecosystem of heuristics, namely trusted external sources that provide a mental shortcut to formulating our own opinions.

By a similar token, cognitive research suggests that humans are biologically programmed to follow the crowd by feel-good chemicals in the brain. In a study by neuroscientists in the Netherlands, for instance, a group of respondents were asked to rate hundreds of faces by their attractiveness. Brain scans showed that dopamine levels dipped when participants diverged from the consensus, who often then changed their ratings to align with that of the wider group.

In a related field, the famous Stanford Prisoner Experiment proposed some powerful conclusions about the innate tendency to conform with group behaviour and allow it to influence or corrupt our own.

In other words, humans are wired to fall in line with consensus, and social media has created a vastly amplified, polarising, dumbed down version of the process.

Hybrid warfare and the attention economy

Perhaps in a case of bad historical timing for the West, the social web shares powerful chemistry with the wider evolution of populism in America and Europe, where economic gloom and a neoliberal backlash have galvanised the appeal of radical alternatives to the status quo.

This combination has given rise to a kind of omnipresent Western counterculture, which may yield endless positive impact on politics. But it also remains vulnerable to exploitation by hybrid warfare operators. Popular suspects include Daesh, the al Qaeda off-shoot, and the Russian Government, which stands accused of meddling in the 2016 US Election with divisive online propaganda that piggybacked the filters and algorithms of target audience engagement. From a tactical perspective, both kinds of narrative can be said to utilise the modish sentiment of victim empowerment – against a caricature of decaying, neo-imperial Western establishment.

Bad online habits could also be contagious. Traditional media outlets may now compete for attention by lowering the tone and dialling up the partisanship. Or the endless fever of social media could be eroding capacity for long-term strategic thinking, as policy-makers are distracted by short-term preoccupations of cyber cut and thrust.

"Sheer volume could render effective moderation of mass sharing-platforms unworkable"

At a more social level, Silicon Valley insiders have suggested how the fundamental characteristics of social media were designed to exploit the narcissistic vulnerability within human psychology, specifically by getting people hooked on social validation through likes, follows, shares and other cyber-dings of “pseudo-pleasure”.

Potential side-effects include heightened pressure for attention and popularity, particularly among the young, and a sense of inadequacy compared with the airbrushed lives of others. It may also be generating a kind of continuous partial attention syndrome, which eats away at concentration, productivity and mental well-being.

The ultimate purpose of those cyber-dings, say critics, is to monopolise attention, which is then monetised by charging retailers for the right to pad our screens with adverts. This kind of online marketing has become highly precision-targeted in recent years, based on reams of data being quietly and constantly harvested. Such information is used to personalise and improve our online experience but has also led to growing concerns that we are losing control of our personal data, and that social media is ultimately big advertising business masquerading as a civic service.

The new solutionism

In short, there is much good in social media, which holds enormous power to keep people informed or to spur civic engagement and community action. But societal repercussions abound, for which there are few easy solutions.

Under pressure from the European Union, for example, big tech companies have become more active in removing illegal and extremist content. But sheer volume could render effective moderation of mass sharing-platforms unworkable, at least to the extent that many now demand.

For a sense of scale, notes David Aaronovitch (£), some 200 billion tweets are posted every year - or about 6000 tweets per second - while similar amounts of video are uploaded to YouTube in a month as were transmitted by every American TV network in the last three decades. Auto-detection technology may be helping. But it could also prove too blunt for free speech activists in distinguishing illegal from merely distasteful.

Facebook is pursuing a range of new measures, such as providing additional context on newsfeed articles, with information on publisher, dissemination and additional perspectives. But this begs the question of whether educational curiosity can suddenly be nurtured into precedence over the typical filter-bubble mentality and browsing habits of mass infotainment consumption.

"Some counter there is nothing new in the civic problems of Web 2.0"

Further measures by the company include new rules on transparency around funding, origination and searchability of adverts. But this raises challenges in blanket efforts to moderate content on a global scale, such as putting lives and legitimate activity at risk when human rights organisations post content in undemocratic societies.

Others have suggested social media companies become more proactive in promoting positive or calmer content, including re-directs or pop-ups that link away from hostile content. But this again raises issues of scale and neutrality - i.e. who gets to be the arbiters of truth.

For another possible solution on digital political advertising, US lawmakers have proposed the Honest Ads Act. This would obligate social media to follow standard rules on advertising transparency, which apply to more traditional media. Critics wonder, however, if it may be too limited in dealing only with ads that support specific election candidates, rather than more general content.

On the problem of fake news, Wikipedia founder Jimmy Wales believes the wiki model could inform the solution. His new initiative, WikiTribune, proposes a hybrid form of citizen journalism that combines a larger online community of collaborators working with a smaller team of professional journalists, paid for by crowd-funding rather than advertising. It is early days for the project but sceptics wonder if it can ultimately counter the syndrome of bad content outperforming good in the wider cyber news sphere.

As inventor of the World Wide Web, Sir Tim Berners-Lee is leading a project called Solid at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, which aims to radically change the model of online data ownership. Our current one is based on an “all-or-nothing approach to data sharing”, he laments, where a company owns all the data you generate while using their services, creating a scenario of ‘vendor lock-in’.

One new approach, Berners-Lee contends, could be an app that allows users to decide where they store their data, including in private cloud storage, for which companies would need permission in order to access. Not only would this empower consumers, he believes, but would also help to level the playing field for smaller companies and start-ups, which would no longer need to amass extensive backends of stored data to compete with the tech giants.

In the British context, former Liberal Democrat MP Julian Huppert has similarly suggested that we need a Digital Bill of Rights, which would legally enshrine citizen ownership of data and protection from third-party bulk collection, whether by companies or governments.

Nothing has changed?

Analysts have questioned the extent to which online content can claim the decisive role in political polarisation over recent years. Some also counter that there is nothing new (£) in the civic problems of Web 2.0.

After all, surely every revolution in communications technology has stirred a sense of moral panic. By a similar token, propaganda and the rowdy polis were ever thus, while the tug of war between direct and representative democracy is as old as Plato.

What is plainly new, however, is a quantum, digital increase in the power of public opinion, which appears capable of routinely overwhelming informed or civilised discourse, while providing propagandists and autocratic actors, both state and non-state, with unprecedented tools for gaming pluralism.

It may simply be that both the good and bad genies of social media are now permanently out of the bottle. As Facebook’s own product manager for civic engagement recently stated, "I wish I could guarantee that the positives are destined to outweigh the negatives – but I can’t." Either way, 2017 seemed like a turning point for both public and political attitudes to the social web, which leaves it facing new threats of regulation from both European and American lawmakers.

Accordingly, much of the conversation around defining Web 3.0 has so far been focused on technological aspects, such as artificial intelligence and the Internet of Things. It is not unlikely, however, that what really defines the next age of Internet is a lasting prejudice towards the digital wild west of Web 2.0, and a set of protracted battles: over who controls access to your data; who can best game the cyber social swarm; and where the division lies between moderation versus censorship and regulation versus self-remedy by Silicon Valley.

If public culture relies on a delicate balance of power between people and institutions, then it seems the raw force of cyberspace has significantly upset that balance within democratic society.

Perhaps forever.

Footnotes:

1. Walter Lippmann, Public Opinion (Minnesota: Filiquarian Publishing LLC, 2006), pp.19-20.

Methodology:

YouGov-Cambridge fieldwork was conducted online between 23–24 October, 2017 (see results), with a total sample of 1680 British adults, and between 4-5 January 2018 (see results), with a total sample of 1628 British adults. The data have been weighted and results are representative of all British adults aged 18 or over.